Imagine the novelization of this:

And you’ve pretty much got it.

- Michael Moats

Filed under book review, books, n+1, review

When Marco Roth was a child, his father was diagnosed with AIDS. The family tried to keep it secret because—this being the 80s—the only plausible explanations were gay sex or dirty needles. Eugene Roth strenuously denied both. He was a doctor, a bourgeois intellectual, an atheist Jew on the Upper West Side, and he claimed to have been accidentally stuck with an HIV-infected needle while treating a patient.

The quiet agony of helping your father die and the unusual pain of being forbidden to talk about it with anyone are ostensibly the subjects of Roth’s memoir, The Scientists. But they only take up the first third of the book. Roth offers a boy’s-eye view of the cluttered bookshelves and claustrophobic social circles of a bygone era in Manhattan, when people who weren’t billionnaires lived on Central Park West and raised their children on classical music. There is real drama here, as Eugene Roth tries to be a good father even though his impending death is the strongest odor in the house. Father and son tend to sit around reading medical journals, looking for a scientific narrative that will make sense of the disease that is destroying their family.

Roth writes in measured, weathered prose, as if he’s trying to rise above the contemporary expressions that would pin him to a particular time and place. Although he uses the first person and present tense, his brain seems to function in the third person, past tense. He crafts little composite scenes to represent his broader memories, and he paints a portrait of his own socioeconomic class by fixating on details like the family’s furniture. The Scientists feels like a classic 19th century novel about the atristocracy and one boy’s coming of age that has been crammed into a navel-gazing 21th century memoir. In a 19th century novel you can feel sympathetic toward a protagonist who is described as precocious. But when an author repeatedly calls himself “precocious” in a 21th century memoir, you want to chuck the book at a wall.

After his father dies, Roth’s aunt publishes a book (because everyone in this memoir is either a brilliant scientist or a successful artist) implying that Eugene Roth might have been gay. This sends our author into a fit. He feels certain the allegation is untrue and compelled to find a way to disprove it. There are shades of homophobia here, but Roth explains himself by saying that if his father was, in fact, gay, then Roth’s whole childhood—with loving, heterosexual parents—was a sham. So begins Roth’s investigation of his father, which takes up the bulk of the memoir. Continue reading

Filed under "Non-fiction", book review, books, n+1, review

I’ve read eleven of the thirteen print issues of n+1 cover-to-cover, and for the most part I’m glad I did. But if you already suspect that n+1 is a magazine with its head up its own ass, you can cite the current issue as evidence. Keith Gessen and Benjamin Kunkel peel off a few pages from their works-in-progress (a translation of an essay on Russian poetry, and a play about a Benjamin Kunkel type, respectively), the editorial staff goes gaga for Occupy Wall Street (“Everything felt so real at that moment—our position within this greater structure thrown into ecstatic relief.”), and, in true n+1 fashion, a series of aspirants and outsiders, who seem to believe that a first-rate undergraduate education is all the intellectual preparation one needs in order to master the universe, offer dry remarks on high culture, their voices wet with envy. This issue contains an essay by James Franco that wasn’t even written by James Franco. The would-be saving grace is a piece by associate editor Christopher Glazek that synthesizes much of the recent literature on the prison crisis in the United States, and argues for the abolishment of our entire system. But there is much better stuff being published directly on n+1’s web site, which perhaps confirms that n+1 has become more of a brand than a magazine.

- Brian Hurley

Filed under n+1

The Art of Fielding tells the tale of college baseball prodigy Henry Skrimshander, a shortstop who loses his handle on perfection and goes from errorless to ineffectual in the time it takes a ball to travel from between second and third base into the dugout. Set in a fictional liberal arts school in the Midwest, Henry’s downfall acts as a hub around which four other characters revolve. The venerable college president, one Guert Affenlight, finds himself in an affair with a young male student, Owen Dunne. Skrimshander’s mentor and best friend, Mike Schwartz, fails to get into the five top law schools while watching his protégé become a failure. Mixed in with the group is Affenlight’s brilliant but lost daughter, Pella, who comes to the story from a failed marriage.

The novel is unassailably nerdy about literature. Moby Dick, or “The Book” as it is sometimes called, features prominently in the setting. The college baseball team is called the Harpooners, a statue of Herman Melville stands watch on campus, and the sorority girls wear t-shirts with Melville-inspired innuendo. The reader is nearly bruised with all the literary nudging. These flourishes don’t necessarily interfere with the story, but they are representative of Harbach’s style, which can’t seem to decide whether it’s winking or declaiming.

Take the characters names: Henry Skrimshander’s name evokes scrimshaw or the carving of whale ivory. Living up to his name, precious Henry is taken in by the captain of the team and carved into something more beautiful and delicate. The President’s daughter, Pella, is named after a sacked city looted of its treasures, and so this brilliant young woman must rebuild herself. The aging president is named Affenlight, and his biracial love interest is named Dunne. The names here seem to distract more than serve. But Harbach’s characters and their struggles for identity are still believable, and for every eye-roll-inducing appellation he offers a moment of insight.

When Pella begins to fulfill her deep need wash the dishes for Schwartz, whom she has just met, she reflects on how he will take it. “It was a nice gesture to do somebody else’s dishes, but it could also be construed as an admonishment: ‘If nobody else will clean up this shithole, I’ll do it myself!’” This sort of tactical thinking pervades many of the relationships, and is one of the stronger aspects of the novel.

Given his background as an n+1 editor, it is worth noting that Harbach indulges in frequent comparisons between baseball and literature, and how these two forms of entertainment work to capture our attention. “But baseball was different. Schwartz thought of it as Homeric—not a scrum but a series of isolated contests. Batter versus pitcher, fielder versus ball. […] You stood and waited and tried to still your mind. When your moment came, you had to be ready, because if you fucked up, everyone would know whose fault it was.”

Harbach’s extended comparisons between the baseball and literature can be illuminating. He shows how baseball and fiction move along in a deliberate manner, and the spectator finds himself absorbed in the action waiting for something to happen—a major plot point revealed, the bat striking the ball. As the player waits, the spectator waits as well, and we all become vicarious athletes, anticipating, wondering how we would’ve reacted. Fiction forces the reader to do something similar. And while we celebrate those moments when the tension is broken, it is the suspense carrying us from moment to moment that actually fuels our desire to witness a game or story. Of course, Harbach is smart enough to point out pertinent differences.

“Baseball was an art, but to excel at it you had to become a machine. It didn’t matter how beautifully you performed sometimes, what you did on your best day, how many spectacular plays you mad. You weren’t a painter or writer—you didn’t work in private and discard your mistakes, and it wasn’t just your masterpieces that counted […] Moments of inspiration were nothing compared to elimination of error.”

Writers will often speak of their characters taking over, and the novel being the result of witnessing character action rather than choreographing it. But the writer still has ample opportunity to finesse the action through revision. In the split second it takes to throw a ball, there can be no deliberation. In fact, Skrimshander’s failures on the field stem directly from his thinking versus acting. It’s interesting to note that we expect much from our authors because they get an opportunity to edit and hone their works, but we expect even more excellence from athletes, who get no opportunity for revision. Maybe that’s why they get all the girls.

The Art of Fielding takes on much as it investigates the bookends of adult life: the undergraduate experience on one side, and retirement on the other. While Harbach’s prose is deft, his characters intriguing and well-wrought, the novel does little to inspire empathy. Perhaps this is because all the characters are superlative. Skrimshander’s talent as a shortstop is legendary. Pella reads Pynchon at breakneck speed and retains it all. Dunne is so well-read and enlightened that his teammates call him Buddha. One expects great folly from great characters, or at least a fall from grace. But Harbach doesn’t allow them to redeem themselves so much as give them pert escapes. This is especially jarring in a novel with strong allegiances to Moby Dick. In the end we are left with a tale of minor struggle and minor growth, a tale of characters trying to discover where they will find themselves in the territory that lies between their talents, their ambitions, and their desires.

- Paul Gasbarra holds an MFA from UNC Wilmington. He is mostly a schlub who enjoys reading things from time to time and attempting to make intelligent comments about them.

Filed under Hooray Fiction!, n+1

- Fight! (A reminder that critics are frequently wrong, and this is a good thing.)

- One of the best articles we’ve read all year: supposedly a book review of The History of White People,* it frames the history of race in America with examples from Fox News, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Sandra Bullock’s Oscar-winning role.

- As books die a slow death, or emerge as digital butteflies, or whatever, here are some hilarious (?) reports from the field:

Caleb Crain on poaching.

Keith Gessen on freebies (from 2004).

Jonny Diamond on suicide.

.

Filed under Hooray Fiction!, n+1

1.

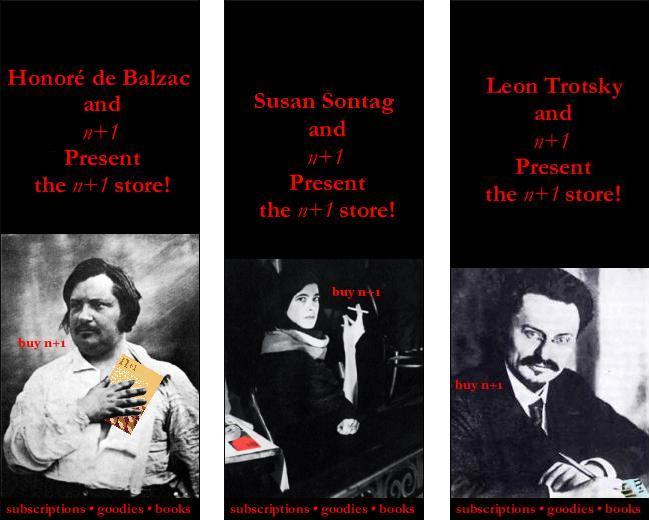

The kids at n+1 have created a neat little ad campaign. They’ve taken old photos of famous dead authors and given them copies of n+1 in Photoshop. The famous dead authors—Honore de Balzac, Leon Trotsky, and Susan Sontag—are supposedly telling you to visit the n+1 store and buy stuff.

Balzac died in 1850. Trotsky died in 1940. Sontag died in 2004, a few months after n+1 published its first issue. As far as we know, Sontag never interacted with the magazine.

We’re not immune to the humor of these ads. They’re a smart critique of consumer culture, with its ubiquitous product spokespeople. At the same time, the ads serve the useful purpose of naming n+1’s favorite authors, which gives you an idea of how to understand n+1.

2.

Two articles about Jonathan Lethem’s new book, Chronic City, compare Lethem to at least a dozen other writers in order to describe his work. They reference Philip K. Dick, Thomas Pynchon, Paul Auster, William Gibson, Anna Kavan, William S. Burroughs, Raymond Chandler, John Barth, J.G. Ballard, Franz Kafka, Woody Allen, and Marvel Comics. That’s a lot of names to drop for one book.

Lethem has self-consciously styled his work on some of his favorite authors. He wants you to recognize their direct influence on him, even if it’s just (as with Pynchon) in the names he chooses for his characters. Critics who write about Lethem want to show you they’ve spotted all his influences.

3.

Clarice Lispector was described by Gregory Rabassa as “that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.”

Clarice resented the comparison—understandably—because she had never read anything by Virginia Woolf.

4.

In Harold Bloom’s famous thesis, all great authors are compelled to create something new because they are intimdiated by the work of their literary forebears, and afraid to simply repeat what’s already been done. Bloom’s criticism describes a kind of literary netherworld, where famous authors, living and dead, exchange techniques and actively develop one another’s ideas, like a pantheon of immortal gods. There may be anxiety on the part of livings authors who contend with the huge influence of their predecessors, but there is also a fantasy, on the part of Bloom and his readers, that all our dearly beloved writers are trading recipes in heaven.

5.

Who benefits when an author is described as a combination of other authors?

When people reference a famous dead author, do you felt like they’re saying, “God is totally on my side?”

Are books just a mix tape of other books?

Should we be anxious about how much good stuff has already been written, or should we brag about how we stole it for our own writing?

Is Leon Trotsky going to rise from his Mexican grave and pulverize the offices of n+1?

.

Filed under Close Reading, Harold Bloom, Jonathan Lethem, n+1, Sam Anderson, sNYROBbery, Speaking Ill of the Dead